Discover Appalachia In Clay County Kentucky

Discover Appalachia In Clay County Kentucky

Appalachia is rich with history, cultural expressions and distinct characteristics such as dialect, music and food. Since its recognition as a distinctive region in the late 19th century, Appalachia has been a source of enduring myths and distortions regarding the isolation, temperament, and behavior of its inhabitants. Early 20th-century writers focused on sensationalistic aspects of the region's culture, such as moonshining and clan feuding, and often portrayed the region's inhabitants as uneducated and prone to impulsive acts of violence. Sociological studies in the 1960s and 1970s helped to deconstruct these stereotypes, although popular media continued to perpetuate the image of Appalachia as a culturally backward region into the 21st century.

Experience the real Appalachia in Clay County, Kentucky...a place of beauty, art, music, nature, unique traditions and friendly, fascinating people.

Early History

Native American hunter-gatherers first arrived in what is now Appalachia over 12,000 years ago. By the time English explorers arrived in Appalachia in the late 17th century, the central part of the region was controlled by Algonquian tribes (namely the Shawnee) and the southern part of the region was controlled by the Cherokee.

European migration into Appalachia began in the 18th century. As lands in eastern Pennsylvania and the tidewater areas of Virginia and the Carolinas filled up, immigrants began pushing further and further westward into the Appalachian Mountains. A relatively large proportion of the early backcountry immigrants were Ulster Scots - later known as "Scotch-Irish" - who were seeking cheaper land and freedom from Quaker leaders, many of whom considered the Scotch-Irish "savages." Others included Germans from the Palatinate region and English settlers from the Anglo-Scottish border country.

Between 1730 and 1763, immigrants trickled into western Pennsylvania, northwestern Virginia, and western Maryland. Thomas Walker's discovery of Cumberland Gap in 1750 and the end of the French and Indian War in 1763 lured settlers deeper into the mountains, namely to upper east Tennessee, northwestern North Carolina, upstate South Carolina, and central Kentucky. Between 1790 and 1840, a series of treaties with the Cherokee and other Native American tribes opened up lands in north Georgia, northeast Alabama, the Tennessee Valley, the Cumberland Plateau regions, and the highlands along what is now the Tennessee-North Carolina border. The last of these treaties culminated in the removal of the bulk of the Cherokee population from the region via the Trail of Tears in 1838.

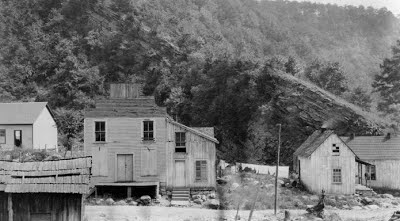

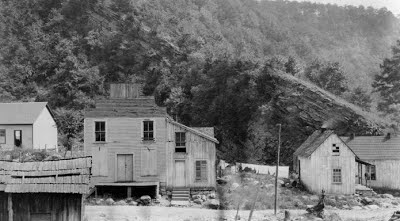

The Appalachian Frontier

The Appalachian Frontier

Appalachian frontiersmen have long been romanticized for their ruggedness and self-sufficiency. A typical depiction of an Appalachian pioneer involves a hunter wearing a coonskin cap and buckskin clothing, and sporting a long rifle and shoulder-strapped powder horn. Perhaps no single figure symbolizes the Appalachian pioneer more than Daniel Boone (1734–1820), a long hunter and surveyor instrumental in the early settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee. Like Boone, Appalachian pioneers moved into areas largely separated from "civilization" by high mountain ridges, and had to fend for themselves against the elements. As many of these early settlers were living on Native American lands, attacks from Native American tribes were a continuous threat until the 19th century.

As early as the 18th century, Appalachia (then known simply as the "backcountry") began to distinguish itself from its wealthier lowland and coastal neighbors to the east. Frontiersmen often bickered with lowland and tidewater "elites" over taxes, sometimes to the point of armed revolts. In 1778, at the height of the American Revolution, backwoodsmen from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and what is now Kentucky took part in George Rogers Clark's Illinois campaign. Two years later, a group of Appalachian frontiersmen known as the Overmountain Men routed British forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain after rejecting a call by the British to disarm. After the war, residents throughout the Appalachian backcountry refused to pay a tax placed on whiskey by the new American government, leading to what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

Early 19th Century

Early 19th Century

In the early 19th century, the rift between the yeoman farmers of Appalachia and their wealthier lowland counterparts continued to grow, especially as the latter dominated most state legislatures. People in Appalachia began to feel slighted over what they considered unfair taxation methods and lack of state funding for improvements (especially for roads). In the northern half of the region, the lowland "elites" consisted largely of industrial and business interests, whereas in the parts of the region south of the Mason–Dixon Line, the lowland elites consisted of large-scale land-owning planters. The Whig Party, formed in the 1830s, drew widespread support from disaffected Appalachians.

Tensions between the mountain counties and state governments sometimes reached the point of mountain counties threatening to break off and form separate states. In 1832, bickering between western Virginia and eastern Virginia over the state's constitution led to calls on both sides for the state's separation into two states. In 1841, Tennessee state senator (and later U.S. president) Andrew Johnson introduced legislation in Tennessee's state senate calling for the creation of a separate state in East Tennessee. The proposed state would have been known as "Frankland" and would have invited like-minded mountain counties in Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama to join it.

The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War

By 1860, the Whig Party had disintegrated. Sentiments in northern Appalachia had shifted to the pro-abolitionist Republican Party. In southern Appalachia, abolitionists still constituted a radical minority, although several smaller opposition parties (most of which were both pro-Union and pro-slavery) were formed to oppose the planter-dominated Southern Democrats. As states in the southern United States moved toward secession, a majority of Southern Appalachians still supported the Union. In 1861, a Minnesota newspaper identified 161 counties in Southern Appalachia - which the paper called "Alleghenia" - where Union support remained strong, and which might provide crucial support for the defeat of the Confederacy. However, many of these Unionists - especially in the mountain areas of North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama - were "conditional" Unionists in that they opposed secession, but also opposed violence to prevent secession, and thus when their respective state legislatures voted to secede, their support shifted to the Confederacy.

Kentucky sought to remain neutral at the outset of the conflict, opting not to supply troops to either side. After Virginia voted to secede, several mountain counties in northwestern Virginia rejected the ordinance and with the help of the Union army established a separate state, admitted to the Union as West Virginia in 1863. However, half the counties included in the new state, comprising two-thirds of its territory, were secessionist and pro-Confederate. This caused great difficulty for the new Unionist state government in Wheeling, both during and after the war. A similar effort occurred in East Tennessee, but the initiative failed after Tennessee's governor ordered the Confederate army to occupy the region, forcing East Tennessee's Unionists to flee to the north or go into hiding. Both central and southern Appalachia suffered tremendous violence and turmoil during the U.S. Civil War. While there were two major theaters of operation in the region - namely the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia (and present-day West Virginia) and the Chattanooga area along the Tennessee-Georgia border - much of the violence was caused by bushwhackers and guerrilla war. Large numbers of livestock were killed (grazing was an important part of Appalachia's economy), and numerous farms were destroyed, pillaged, or neglected. The actions of both Union and Confederate armies left many inhabitants in the region resentful of government authority and suspicious of outsiders for decades after the war.

Late 19th & Early 20th Centuries

After the war, northern parts of Appalachia experienced an economic boom, while economies in the southern parts of the region stagnated, especially as Southern Democrats regained control of their respective state legislatures at the end of Reconstruction. Pittsburgh and its surrounding areas in western Pennsylvania grew into one of the nation's major industrial centers, especially regarding iron and steel production. By 1900, the Chattanooga area and north Georgia and northern Alabama had experienced similar changes due to manufacturing booms in Atlanta and Birmingham at the edge of the Appalachian region. Railroad construction between the 1880s and early 20th century gave the greater nation access to the vast coalfields in central Appalachia, making the economy in that part of the region practically synonymous with coal mining. As the nationwide demand for timber skyrocketed, lumber firms turned to the virgin forests of southern Appalachia, using sawmill and logging railroad innovations to reach remote timber stands.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw the development of various regional stereotypes. Attempts by President Rutherford B. Hayes to enforce the whiskey tax in the late 1870s led to an explosion in violence between Appalachian "moonshiners" and federal "revenuers" that lasted through the Prohibition period in the 1920s. The breakdown of authority and law enforcement during the Civil War may have contributed to an increase in clan feuding, which by the 1880s was reported to be a problem across most of Kentucky's Cumberland region as well as Carter County in Tennessee, Carroll County in Virginia, and Mingo and Logan counties in West Virginia. Regional writers from this period such as Mary Noailles Murfree and Horace Kephart liked to focus on such sensational aspects of mountain culture, leading readers outside the region to believe they were more widespread than in reality. In an 1899 article in The Atlantic, Berea president William G. Frost attempted to redefine the inhabitants of Appalachia as "noble mountaineers" - relics of the nation's pioneer period whose isolation had left them unaffected by modern times.

Feuds

Appalachia, and especially Kentucky, became internationally known for its violent feuds, especially in the remote mountain districts. They pitted the men in extended clans against each other for decades, often using assassination and arson as weapons, along with ambushes, gunfights, and pre-arranged shootouts. Some of the feuds were continuations of violent local Civil War episodes. Journalists often wrote about the violence, using stereotypes that "city folks" had developed about Appalachia; they interpreted the feuds as the inevitable product of profound ignorance, poverty, and isolation, and perhaps even interbreeding. In reality, the leading participants were typically well-to-do local elites with networks of clients who were fighting for local political power.

Modern Appalachia

Modern Appalachia

Income for most mountain families originally revolved around forest farming, based predominantly on family labor which was practiced by the vast majority of the population. Contrary to stereotypes about Appalachian farms, most farms were extremely large and successful. Over the course of time, the division and re-division of the limited land to accommodate the new generations of families reduced the size of farms, thus reducing their commercial productivity. An emphasis on subsistence, rather than commercial agriculture, resulted. The same pattern had occurred in New England in the eighteenth century. What was unique in Appalachia was that subsistence farming lasted so long, owing to growing isolation from the rest of the country as the area was bypassed in the construction of modern means of transportation.

As farming became less profitable, many families moved to new urban and industrial frontiers in the cities of the Midwest. Others moved into the mines and mills that sprang up in Appalachia almost overnight as railroads opened up the region to capitalist industrialization early in the twentieth century.

Logging firms' rapid devastation of the forests of southern Appalachia sparked a movement among conservationists to preserve what remained and allow the land to "heal". In 1911, Congress passed the Weeks Act, giving the federal government authority to create national forests and control timber harvesting. Regional writers and business interests led a movement to create national parks in the eastern United States similar to Yosemite and Yellowstone in the west, culminating in the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee and North Carolina, Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, and the Blue Ridge Parkway (connecting the two) in the 1930s. During the same period, New England forester Benton MacKaye led the movement to build the 2,175-mile (3,500 km) Appalachian Trail, stretching from Georgia to Maine. In February 1937, a national forest for Kentucky was officially established under a proclamation signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Originally named the Cumberland National Forest, the forest was renamed in 1966 as the Daniel Boone National Forest in recognition of the adventurous frontiersman that explored much of this Kentucky region.

By the 1950s, poor farming techniques and the loss of jobs to mechanization in the mining industry had left much of central and southern Appalachia poverty-stricken. The lack of jobs also led to widespread difficulties with outmigration. Beginning in the 1930s, federal agencies such as the Tennessee Valley Authority began investing in the Appalachian region. Sociologists such as James Brown and Cratis Williams and authors such as Harry Caudill and Michael Harrington brought attention to the region's plight in the 1960s, prompting Congress to create the Appalachian Regional Commission in 1965. The commission's efforts helped to stem the tide of outmigration and diversify the region's economies.

The economy of Appalachia traditionally rested on agriculture, mining, timber, and in the cities, manufacturing. Since the late 20th century, tourism and second home developments have assumed an increasingly major role. In 2000-2001, tourism in Appalachia accounted for nearly $30 billion and over 600,000 jobs. The mountain terrain - with its accompanying scenery and outdoor recreational opportunities - provide the region's primary attractions. The craft industry, including the teaching, selling, and display or demonstration of regional crafts, also accounts for an important part of the Appalachian economy.

The mineral-rich mountain springs of the Appalachians, which for many years were thought to have health-restoring qualities, were drawing visitors to the region as early as the 18th century. Along with the mineral springs, the cool and clear air of the range's high elevations provided an escape for lowland elites. The establishment of national parks in the 1930s brought an explosion of tourist traffic to the region.

A Natural Paradise

A Natural Paradise

Stretching nearly 2,200 miles from Alabama in the United States to New Brunswick, Canada, the Appalachian Mountain range is one of the richest temperate areas in the world. Home to over 200 species of birds and well over 6,000 species of plant life, the Appalachian Mountains offer amazing diversity.

Moose inhabit the northernmost reaches of the Appalachians. Weighing in at 1,000 pounds or more, these large animals roam deep woods and wetland areas from Massachusetts into Canada. White-tailed deer are plentiful the entire length of these mountains and can be spotted often. Black bear, bobcats and coyotes are also plentiful. Elk have been reintroduced to the region over the years in parts of Kentucky, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Tennessee. If not observed, their distinctive bugling can sometimes be heard. Wild boars are also a species contained in a smaller region of Appalachia.

An abundance of smaller animals like squirrels, chipmunks, raccoon and opossum live all along the Appalachians. More rare species include fox, porcupine, mink and muskrat. Along with a variety of salamanders and lizards, snakes–both poisonous and non-poisonous–inhabit the woods and rocky areas of the mountains. Many streams and some ponds are fed by springs and their cold water supports trout. Bass, catfish and bream are also plentiful in these waters.

With 255 different species identified, it would be difficult to list all the birds in the Appalachians. Some of the more unique species include whippoorwills and fly-catchers, while songbirds are abundant everywhere in the mountains. Large birds like turkey and grouse are very common, and falcons, eagles and hawks roam the skies in search of prey.

According to a study, 6,374 plant species are documented in the Appalachians. Scientists believe the actual number is five or six times that number. The mountains are well known for azaleas and rhododendrons. Laurel, jack-in-the-pulpit, columbine, trillium and bog laurel cover some hillsides and wild sarsaparilla grows in dry, open woods. Wood nettle can be found growing thick in some fields. Most of these species are spring and summer bloomers but goldenrod, Queen Anne’s lace, wood sorrel and aster can be found in the fall and, occasionally, into early winter.

Forests are described as mixed deciduous with oaks and hickories the most common species of tree found in the Appalachians. A smattering of maples and beech are also in the mix. To the north, spruces and firs are plentiful. The southern end of the mountains is more species diverse than any other forest in North America with basswood, tulip trees, ash and magnolia among the variety.

Music

Music

Appalachian music is one of the most well-known manifestations of Appalachian culture. Traditional Appalachian music is derived primarily from the English and Scottish ballad tradition and Irish and Scottish fiddle music. African-American blues musicians played a significant role in developing the instrumental aspects of Appalachian music, most notably with the introduction of the banjo - one of the region's iconic symbols - in the late 18th century. In the years following World War I, British folklorist Cecil Sharp brought attention to Southern Appalachia when he noted that its inhabitants still sang hundreds of English and Scottish ballads that had been passed down to them from their ancestors. Commercial recordings of Appalachian musicians in the 1920s would have a significant impact on the development of country music, bluegrass, and old-time music. Appalachian music saw a resurgence in popularity during the American folk music revival of the 1960s, when musicologists such as Mike Seeger, John Cohen, and Ralph Rinzler traveled to remote parts of the region in search of musicians unaffected by modern music. Today, dozens of annual music festivals held throughout the region preserve the Appalachian music tradition.

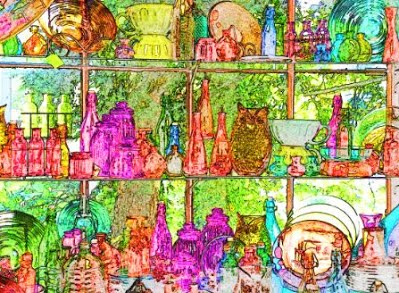

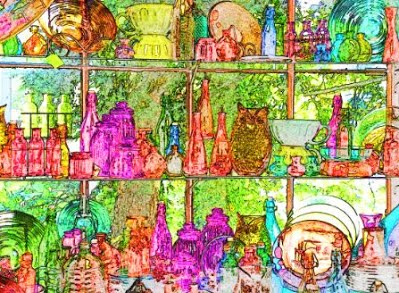

Arts & Crafts

Arts & Crafts

Appalachia’s craft traditions are rich and alive. They are as diverse as our people and can be found in every corner, holler, and river valley of the mountains. The artisans who create them reflect the culture, folklore and entrepreneurial spirit of Appalachia. They are finely hewn and richly expressed, whether inspired from traditional or contemporary influences. The treasured works of hundreds of Appalachians can be found in the many shops, galleries, festivals, and museums throughout Appalachia.

Folklore

Appalachian folklore has a strong mixture of European, Native American (especially Cherokee), and Biblical influences. The Cherokee taught the region's early European pioneers how to plant and cultivate crops such as corn and squash and how to find edible plants such as ramps. The Cherokee also passed along their knowledge of the medicinal properties of hundreds of native herbs and roots, and how to prepare tonics from such plants. Before the introduction of modern agricultural techniques in the region in the 1930s and 1940s, many Appalachian farmers followed the Biblical tradition of planting by "the signs," such as the phases of the moon, or when certain weather conditions occurred.

Appalachian folk tales are rooted in English, Scottish, and Irish fairy tales, as well as regional heroic figures and events. Jack tales, which tend to revolve around the exploits of a simple-but-dedicated figure named "Jack," are popular at story-telling festivals. Other stories involve wild animals. Regional folk heroes such as the railroad worker John Henry and frontiersman Davy Crockett are examples of real-life figures that evolved into popular folk tale subjects. Murder stories, such as Omie Wise and John Hardy, are popular subjects for Appalachian ballads. Ghost stories, or "haint tales" in regional English, are a common feature of southern oral and literary tradition.

Discover Appalachia In Clay County Kentucky

Discover Appalachia In Clay County Kentucky The Appalachian Frontier

The Appalachian Frontier Early 19th Century

Early 19th Century The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War Stereotypes

Stereotypes Arts & Crafts

Arts & Crafts