Native Americans of Clay County & Kentucky

Native Americans of Clay County & Kentucky

Contrary to popular myths, American Indians have lived in Kentucky since time immemorial. When Kentucky was declared the fifteenth state on June 1, 1792, more than twenty tribes, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Chippewa, Delaware, Eel River, Haudenosaunee, Kaskaskia, Kickapoo, Miami, Ottawa, Piankeshaw, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Wea, and Wyandot, held legal claims to the land. At that time, Kentucky was also considered home to the Mingo and Yamacraw, and Yuchi.

For more than 200 years following statehood, American Indians in Kentucky refusing to acknowledge land cession and forced removal were subjected to ecocide, genocide, ethnocide, assimilation, and deprivation. However, they had the will to survive, and survive they did. American Indians preserved their languages, arts, crafts, religions, and representative governments, generation after generation, in locations that have been closely guarded secrets, from mountain cabins and farms, to deep grottos inside caves, remote rock-shelters, and beyond. American Indians in Kentucky concealed their identity in order to survive. It did not stop them, however, from representing their home state in every American war, even when they lacked citizenship and human recognition.

Cultural Contributions

American Indians domesticated a plethora of plants including the bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria), the gourd-like squash (Cucurbita pepo), the sunflower (Helianthus annuus), maize (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus), cushaw squash (Cucurbita argyrosperma), and tobacco (Nicotiana species). In addition to cultigens, American Indians practiced silvaculture of nut-bearing trees such as black walnut, pecan, and the chestnut. Aside from the economic significance of these cultigens and masts, they are literally helping to feed people around the world today.

American Indians recycled of all of their natural resources including those obtained from plants, animals, and the earth. Most important of these, they managed their water resources by creating and maintaining sustainable landscapes that provided irrigation to their crops and villages. American Indians were the original environmental stewards.

The political system of the United States was modeled after the confederacies and leadership formed among and between American Indian tribes during the eighteenth century. Decisions were made of the people, by the people, and for the people through consensus. Power and prestige among American Indians came not from the accumulation of personal material wealth, but from how much was given away. In this vein, everyone was

cared for. No one went hungry, unsheltered, or unclothed. Each person had a purpose and role in society.

Most of the major roads in Kentucky were built on American Indian trails. For example, US 27 was known as the Great Tellico Road and US 25 was known as the Warriors road, as was significant portions of US 421. Much of Daniel Boone’s Wilderness Road was actually an American Indian trail used for seasonal migration and trade.

American Indians used a wide variety of therapeutic plants, many of which have been synthesized and are key ingredients in modern western medicine.

American Indians have served in the armed forces of the United States in every war including the American Revolution. They have fought and died for their country even when they were not considered human beings or citizens.

American Indian Identity

American Indians living in Kentucky have intermarried outside their tribe since time immemorial. Unfortunately, many people today still hold antiquated stereotypes about American Indian identity and use mixed-blood terms such as full-bloods, half-bloods, and quarter-bloods. These modern misconceptions of biology and culture can be traced to the very beginning of the state. In the complete absence of a single genetic laboratory, the Shawnee Treaty of 1831 was used to define and enforce who was a “real” American Indian and who was not. The treaty gave Joseph Parks, a reported quarter-blooded Piqua Shawnee, entitlements including six hundred and forty acres of land. Park’s blood quantum was assumed and assigned to him rather than reflecting his actual genetic background or cultural identity. Unfortunately, the Shawnee Treaty of 1831 became the standard for identifying American Indians in Kentucky. Today, rather than an understanding of American Indian people or their culture, most people have a stereotype about them. For example, many people still believe that American Indians in Kentucky lived in cave or tipis. At the time Kentucky was declared a state, American Indians were actually living in log cabins, multi-story wooden homes, and brick houses. Failure to recognize American Indians and their tribal cultures has led to the destruction of many of Kentucky’s historic and cultural resources.

Historical Myths

For more than 200 years, American historians have argued that the American Indians never lived in Kentucky. Instead, they portrayed Kentucky as either a middle ground used by all tribes for hunting or the center of many dark and bloody disputes. John Filson, an opportunistic investor, land speculator, and entrepreneur, created this myth and many others in a book, The Discovery, Settlement, and Present State of Kentucke, published five years after his death in 1788. The book included an account of American Indians inhabiting within the limits of the thirteen United States including their manners and customs, and reflections of their origin. Filson’s book falsely explained that there were no American Indians living in Kentucky, but they were located in the adjacent states. Filson further emphasized that American Indians had no valid claim to Kentucky because it was originally settled by an ancient white race that greatly predated the Indians. Ironically, the very people Filson claimed did not live in Kentucky killed him.

Filson’s book was widely printed and circulated in England, France, and Germany as a way to entice Europeans to immigrate to the United States and settle in Kentucky. To further allure them to this new land of opportunity, Filson created a story about an American Indian silver mine. His fictitious story emphasized that Kentucky was a land filled with riches just waiting to be taken. Unfortunately, all of Filson’s myths about American Indians were perpetuated and elaborated upon in subsequent books on the history of the state such as Lewis Collins’ 1847 Historical Sketches of Kentucky, Richard Collins’ and Lewis Collins’ 1874 History of Kentucky, Bennett Young’s 1910 The Prehistoric Men of Kentucky, and W. D. Funkhouser’s and W. S. Webb’s 1928 Ancient Life in Kentucky and are still being taught in some quarters of the state today.

European Contact

European Contact

Prior to European contact, Kentucky was inhabited by Algonquian (e.g., Delaware, Miami, Shawnee), Iroquoian (e.g., Cherokee, Haudenosaunee, Mingo, Wyandot), Muskogean (e.g., Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek), and Siouan (e.g., Saponi) speaking peoples. The Cherokee were the first people to come in contact with Europeans. The earliest known contact with Europeans occurred in 1540, when a party of Cherokee warriors successfully defended their northwestern border against the advances of Hernando DeSoto and his Spanish soldiers. They forced the Spanish to retreat from Kentucky to the north side of the Ohio River at present-day Fort Massac, Illinois.

Interestingly, the word Cherokee comes from the 1557 Portuguese narrative of DeSoto’s expedition, which was then written as chalaque. It is derived from the Choctaw word, choluk, which means cave. Mohawk call the Cherokee oyata’ge’ronoñ, which means people who live in caves or in the cave country. In Catawba, the Cherokee are called mañterañ, which translates as the people who come out of the ground. Kentucky is a land of caves and home to the longest cave in the world. Kentucky caves are full of evidence of Cherokee people, from salt and crystal mines to exploration and habitation. As the Cherokee explored and settled in Kentucky, they came across the entrances of great caves, some of which were filled with mineral resources that extended many miles underground. They ventured into caves in search of protection from the elements, to mine minerals, to dispose of their dead, to conduct ceremonies, and to explore the unknown, as indicated by the footprints, pictographs, petroglyphs, mud glyphs, stone tools, and sculptures they left behind. Wherever the Cherokee found a dry cave in Kentucky with a reasonably accessible opening, they entered and explored it systematically.

Before European colonization, Kentucky was a significant part of the Cherokee country, representing the northern quarter of the Cherokee Nation since time immemorial. Its boundaries extended to the Ohio River in the north, the Cumberland River in the west, and the Great Kanawha River in the east. By the end of the American Revolution, the northern boundary of the Cherokee country was moved southward to encompass the land below the Cumberland River. Eventually, some 38,000 square miles of Cherokee land in Kentucky was ceded to Great Britain and the United States.

After the British arrived on the present site of Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, there was continuous contact with Cherokee in Kentucky as traders strengthened their alliances and worked their way into the Appalachian Mountains. Perhaps the earliest evidence of an English trader with Cherokee in Kentucky is in Wolfe County, where a date of 1717 occurs with traditional symbols of Anitsisqua, the Cherokee Bird Clan, incised on a sandstone outcrop overlooking Panther Branch.

Changing Alliances

Changing Alliances

Cherokee claims to Kentucky were seriously challenged when the Tuscarawas joined the Haudenosaunee, a confederacy of Iroquoian speaking peoples that included the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas in 1722. Expanding by alliance and conquest, they penetrated deeply into the state. The newly formed Six Nations took over control of all of the land north of the Cumberland River.

By 1729, the Shawnee were serving as guides into northern Kentucky for the French military who considered Kentucky part of New France. At this time, the Cherokee were busy fighting the Choctaw, Creek, and Yamasee to the south for their British allies. As a gesture of thanks, Sir Alexander Cuming took principal Cherokee Chiefs to England with him in 1730 including Attakullakulla, Clogoittah, Kollannah, Onancona, Oukah Ulah, Skalilosken Ketagustah, and Tathtowe. Although this visit strengthened allegiance with the British, the Cherokee population in Kentucky and elsewhere was cut in half by smallpox just eight years later making it difficult to defend their northern borders. To make matters worse, the Creek and Choctaw had allied themselves with the French.

At the onset of the French and Indian War in 1750, Cherokee, Delaware, Shawnee, and Wyandot leaders seeking inter-tribal peace traveled back and forth through Kentucky on the Great Warrior Road in route to council meetings with representatives of the Six Nations. While the Cherokee were granted permission from the Six Nations to return to their land north of the Cumberland River, it was a political exchange for their partisan position against the French and all villages sympathetic to French traders. As part of the peace agreement, Shawnee families began to spend winters with the Cherokee, and warriors began to spend time with the Shawnee.

During the French and Indian War, between 1754 and 1763, blockades cut off salt shipments from the West Indies. Salt springs and licks in Kentucky became an important resource to the colonists. Shawnee made salt at Big Bone Lick in Boone County and Blue Licks in Nicholas County in the north. The Cherokee made salt and buried their dead along Goose Creek near the mouth of Collin’s Creek in Clay County. The abundance of salt in Kentucky, north and south, did not escape the eyes of the Europeans and later became an issue of national security.

With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France gave up all mineral resource and land claims to Kentucky. In exchange for their help during the war, the British victors proclaimed that Kentucky was to be recognized as Indian Territory and no person could make a treaty with the Cherokee or buy land from them without their permission. While the treaty of 1763 allowed the Cherokee to retain all of their land in Kentucky, their possession was short-lived.

In 1768, the British superintendent of Indian Affairs convinced the Cherokee to cede their holdings in what is today the state of Virginia to prevent conflicts with encroaching colonists. British representatives insisted on the negotiation of a new treaty on October 18, 1770, which moved the northeastern boundary of Cherokee country from the New River of West Virginia to the land within the extreme western corner of Kentucky, today known as Pike County. Two years later, Great Britain requested yet another treaty to purchase all of the land between the Ohio and Kentucky rivers.

Entrepreneur and colonial judge Richard Henderson, his agent Daniel Boone, and other private citizens met with Cherokee Chiefs along the Watauga River on March 17, 1775. Henderson and Boone illegally negotiated the cession of all of the land in between the Kentucky, Ohio, and Cumberland rivers to the privately owned Transylvania Company. Although it has become known as the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, the entire event was in direct violation of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. On behalf of England, the colony of Virginia, which then included Kentucky, revoked the treaty. However, it did not stop Boone and the Transylvania Company from creating the Wilderness Road, which opened the way for an unstoppable and unlimited flow of European immigrants into Kentucky and in direct conflict with the Cherokee.

The Treaty of Sycamore Shoals was negotiated just one month before the beginning of the American Revolution. Many American Indians living in Kentucky supported the British through the war and beyond to 1794. Following the example of the Delaware Chief, Coquetakeghton White Eyes, who served as a guide and lieutenant colonel in the American army, a number of mixed-blood Cherokee living in Kentucky, such as King David Benge and Jesse Brock, agreed to serve as scouts. At the decisive Battle of Kings Mountain, October 7, 1780, there were Cherokee warriors from Kentucky fighting on both sides.

By 1782, individual Cherokee political alliances had become extremely complex. Some traveled to St. Louis, Missouri to seek protection from the Spanish government, while others moved north and joined the Shawnee on the Scioto River getting supplies and council from the British military. At the same time, representatives of the Chippewa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot traveled to the Cumberland River valley to council with the Cherokee about joining them in an all out war against the United States.

The American Revolution ended on September 3, 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The Cherokee were not consulted and many did not recognize England’s cession of Kentucky to the United States. To make matters worse, a group of Tennessee colonists illegally created the State of Franklin with John Sevier as their Governor. On May 31, 1785, Major Hugh Henry, Sevier, and other representatives of the self-declared state met with Cherokee Chiefs to negotiate the "Treaty of Dumplin Creek," which promised to redefine and extend the Cherokee boundary line. Because the United States government did not recognize the State of Franklin, the Treaty of Dumplin Creek was deemed illegal. Seiver and his Franklinites engendered a spirit of distrust between all subsequent treaty-makers and the Cherokee, which led to many bloody conflicts and, ultimately, genocide in Kentucky.

The first official treaty between the United States and Cherokee Nation was negotiated at Hopewell, South Carolina on November 28, 1785. The Hopewell Treaty included the cession of all land in Kentucky north of the Cumberland River and west of the Little South Fork. Although Cherokee Chief Corn Tassel, brother of Doublehead, signed the treaty, other clan chiefs did not. The Hopewell Treaty began a war between the European settlers and the Cherokee living in the Cumberland valley. They fiercely resented the intrusion of immigrants and were determined upon their expulsion or extermination.

Many Cherokee warriors from Kentucky joined into a confederacy with the Delaware, Miami, Shawnee, and Wyandot who continued to be supplied and encouraged by England to defeat the newly formed country. For the next thirteen years, they waged war upon the settlements in their land. Although most American history books do not include this war, it was the first to be declared by Congress in 1790. It has been referred to as George Washington’s Indian War in the struggle for the old northwest. In December of 1790, Kentucky settlers petitioned Congress to fight the Cherokee in whatever way they saw fit. A Board of War was appointed, and on May 23, 1791, it authorized the destruction of Cherokee towns and food resources by burning their homes and crops.

In an attempt to make peace with the Cherokee, and redefine the new boundary lines in Kentucky, the United States negotiated the Treaty of Holston on July 2, 1791. It restated that the Cherokee land in Kentucky was restricted to the area east of the Little South Fork and south of the Cumberland River. The treaty was signed by Kentucky born Cherokee Chief Doublehead, his brother, Chief Standing Turkey, their nephew, John Watts, and witnessed by Thomas Kennedy, a representative of Kentucky in the Territory of the United States South of the Ohio River. Unfortunately, the boundary line remained unclear and disputed by Cherokee not present at the treating signing, and the fighting continued for the next seven years. One of the last skirmishes in Kentucky occurred at the salt works and Cherokee burial grounds on Goose Creek in Clay County, on March 28, 1795.

The Treaty of Greenville, negotiated in Ohio on August 3, 1795, ended the war between the United States and the confederacy. The treaty was made between Major General Anthony Wayne, commander of the army of the United States, and the Chippewa, Delaware, Eel River, Kaskaskia, Kickapoo, Miami, Ottawa, Piankeshaw, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Wea, and Wyandot. Although the treaty tried to settle controversies and to restore harmony and friendly intercourse between the United States and all American Indian Nations, Cherokee chiefs, shamans, and warriors were not permitted to attend. All of the Cherokees who were living north of the Ohio River subsequently returned to their homes in southern Kentucky.

On October 2, 1798, the first Treaty of Tellico was negotiated with the Cherokee Nation. It allowed for safe passage of settlers using the Kentucky road, running through Cherokee land between the Cumberland Mountain and the Cumberland River, in exchange for hunting rights on all relinquished lands, a further refinement of the Holston Treaty of 1791. By 1803, the demand for salt on Cherokee land in Kentucky dramatically increased when England seized American ships involved the salt trade. In 1805, the remaining Cherokee land in Kentucky was considered crucial to the national security of the United States. Between October 25 and 27, 1805, Kentucky Cherokee Chief Doublehead singed the final Treaties of Tellico, ceding the land south of the Cumberland River. Feeling that they had been betrayed and sold out, Doublehead was assassinated on August 9, 1807 in McIntosh Tavern, Hiwassee, Tennessee, by Charles Hicks, Alexander Saunders, and Major Ridge—his own people.

After the last tribal lands were ceded in 1818, Richard Mentor Johnson, a Kentucky born United States Vice President under Martin Van Buren, 1837-1841, acting on behalf of the state of Kentucky, opened the Johnson Indian Academy in Scott County, under the auspices of the Baptist Board of Foreign Missions. Its purpose was to hasten the civilization process of American Indians by educating the sons of Chiefs of Tribes that had ceded land in Kentucky. In 1825, the school received federal funding through the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit, and the name was changed to the Choctaw Academy. The school closed in 1845 from the mismanagement of federal funds. Many American Indian families that had moved to Scott County to be close to their children remained as a painful alternative to removal to Indian Territory in the West.

Many American Indians who remained in Kentucky acculturated into the existing communities throughout the state. The Sizemore family of Clay County is an old and well documented example. In January 1822, the Clay County Court was informed that a man named Pickney from Alabama came to the home of James Sizemore and dropped off his five year-old mixed-blood Creek son named George. His mother was a Creek named Anny. Five years earlier, 1817, about the time of George’s conception, Major General Pickney presented and liquidated the Creek treaty at Fort Jackson, Alabama. One year later, on December 8, 1818, Author Sizemore testified in the Claims of Friendly Creeks Paid Under the Act of March 3, 1817. Four years after that, Pickney arrived in Clay County at the home of James Sizemore with a Creek child name George. George was given the surname Sizemore and his many descendants lived as traditional American Indians. For some, this livelihood resulted in prejudice and, in some cases, death.

Chief Red Bird

Chief Red Bird

Red Bird, Dotsuwa, was a Cherokee who lived and died in what is known today as Clay County, Kentucky, before and after European colonization, a time when the Cherokee Nation extended to the Ohio River in the north, the Cumberland River in the west, and the Great Kanawha River in the east.

The well-known Warrior’s Trail, today known as US route 421, ran from Florida to Michigan, and served as an important trade route for many thousands of years. It passes through Clay County. Remnants of the trail survive to this day, running up Goose Creek to the mouth of Otter Creek, up Otter Creek, and down Stinking Creek. Other segments of the trail are present on the bench tops of mountains along the Middle Fork.

Clay County provided Red Bird and his people with a bounty of game, fish, and natural resources, many considered sacred to this day. There was an extremely large natural gas seep with jets that were several feet high and burned day and night over an area of more than twenty-square-feet, creating a mystifying fog in the surrounding hills in places today known as Burning Springs and Fogertown. Along Goose Creek, in present day Manchester, there were salt licks and springs where salt was manufactured and collected, ceremonies conducted, and the dead were buried. Red ochre, the mineral hematite, was used to make paint for ceremonies of life and death. It is also the namesake of the Cherokee family clan, Ani Wodi. Cherokee mined this ore in Clay County on a small parcel of land between the South and Middle Fork rivers.

By the second half of the eighteenth century, Europeans intruded the area around Clay County. In 1769, expeditions including those of Daniel Boone and John Stewart came into the area. It was the first of Boone’s many encounters with William Emory Jr., also known as Will, a redheaded Cherokee who frequently traveled with the Shawnee. Will was the son of England born William Emory Sr. and Cherokee born Mary Grant. She was the daughter of Cherokee Elizabeth Idui Tassel and Scotland born Ludovic Grant. Another expedition, led by James Knox in 1770, met with a band of Cherokee on the Rockcastle River. Knox and his men recognized their leader as Dick, pronounced Dix, who frequented the lead mines on the Holston River. Realizing Knox’s party was in need of food, Dick suggested they cross Brushy Ridge and hunt for game in his river valley, known today as Dix River in Rockcastle County. He ended the conversation with Knox’s party by saying, “kill it, and go home.” While initial contact with the Cherokee was peaceful, increasing numbers of Europeans strained relations and fighting broke out in February 1772 on Station Camp Creek. With the increase in European encounters, the Cherokee had trouble maintaining control over Kentucky, especially in the land north of the Cumberland River valley.

Following the Treaty of Paris and the end of the American Revolution in 1783, Boone personally wanted the Wilderness Road to cut through the Cherokee’s sacred ceremonial and burial ground on Goose Creek because he knew the economic importance of salt. While Boone was never given a contract to extend the Wilderness Road to Goose Creek, he was employed as a Deputy Surveyor of Lincoln County, today known as Clay County, to survey 50,000 acres of Cherokee land for Phillip Moore, James Moore, and John Donaldson. In 1784, with the assistance of William Brooks, Septimis Davis, and Edmund Callaway, Boone began surveying one mile from the mouth of Sextons Creek. As the surveys increased so did the conflict between the Europeans and Cherokee.

Red Bird spent a good deal of his time with his friend Will in the vicinity of two rockshelters on the east and west banks of the Kentucky River, a stretch of the upper headwaters, known today as the Red Bird River in Spurlock. The opposing shelters are strategically located in a narrow constriction of the valley overlooking a shallow river crossing where the fishing is good and game animals can be easily dispatched. Both shelters are well marked with traditional Cherokee symbols—engraved images of the Bird, Wolf, and Deer clans. It was in this setting that Red Bird and Will were murdered, brutally and maliciously tomahawked to death by two men from Tennessee, Edward Miller known as Ned, and John Livingston, known as Jack. Livingston lost family members at the hands of the redheaded Red Paint Clan Cherokee, Robert Benge, also known as the Bench. He was the son of John Benge and Wurteh Watts, a brother of Sequoyah, and the first cousin of King David Benge who lived nearby.

In 1788, Robert Benge successfully defeated John Sevier during his attack on the Cherokee village of Ustali on the Hiwassee River in North Carolina. It was during this battle that Thomas Christian coined the term “nits make lice” as he brutally murdered a Cherokee child. It was an incident that Robert Benge never forgot. Robert Benge repeatedly attacked the families of Sevier’s militiamen, including the Livingston homestead near Moccasin Gap, Virginia. Paul Livingston and his brother Henry Livingston, sons of Sarah and William Todd Livingston, were officers in the Holsten Militia and thus considered enemies of the Cherokee. Benge’s first attack occurred on August 26, 1791, which resulted in the capture and death of Mrs. Livingston, the daughter of Elijah and Nancy Ferris, who were also killed. The second attack occurred on July 17, 1793, when Robert Benge captured a woman enslaved by Paul Livingston. Robert Benge’s final and best-documented attack began about 10 AM, on April 6, 1794.

Robert Benge and a party of Cherokee warriors tomahawked Sarah Livingston and three children, and took Elizabeth Livingston, wife of Peter Livingston, her sister Susannah, known as Sukey, and their surviving children as well as all of the adults and children enslaved by the Livingston family. On April 9, 1794, Lieutenant Vincent Hobbs of the Lee County Militia hunted down and killed Robert Benge and freed his captives.

John Russell and his men, who were traveling with Hobbs, pursued Robert Benge’s surviving Cherokee warriors to the shallow river crossing in the headwaters of the Kentucky River, in present day Clay County. Russell and his men took refuge nearby and shot to death two of the escaping Cherokee warriors and badly wounded another as they tried to cross the river. Since then, the site was known as a place where the Cherokee could be found and killed. It was where John (Jack) Livingston and Edward (Ned) Miller found and cruelly murdered Red Bird and Will.

John Sevier was inaugurated Governor of Tennessee on March 30, 1796. As governor, it was his sworn responsibility to enforce the treaty between the Cherokee and the newly formed United States of America. He was bound by office to take responsibility for any and all violations against the Cherokee by the citizens of the State of Tennessee. He consistently met this responsibility with denial to the Cherokee with added threats of war and removal. One of his first correspondences to the Cherokee Nation was written on April 2, 1796 addressing a complaint that a Red Bird had been killed. On July 7, 1796, Sevier wrote a follow up letter to the Cherokee Nation explaining that he should not be held responsible for murders that occurred under the previous administration of Governor Blount and in the state of Kentucky, not Tennessee. By January 1797, Sevier had been informed that Red Bird was murdered. It was also clear to Sevier that the murder had been committed by citizens of the State of Tennessee, which were under his jurisdiction. As a trained lawyer,

Sevier knew that he had to respond, as the incident was a direct violation of a United States treaty with the Cherokee. On January 12, 1797, Sevier wrote a letter to Cherokee agent Silas Dinsmore to be read aloud to the Cherokee. Initially, Sevier wanted to express his condolences for the murder of Red Bird by stating that he doubted any of his people would do such a thing. However, he later decided to strike out this section of the letter. It was not until February 1797 that Sevier clearly understood that it was not one, but two Cherokee that were murdered—Red Bird and William Emery. On February 10, 1797, Sevier wrote another letter to the Cherokee Nation. While it does present condolences for the murders, he denies that they were committed by anyone under his authority. Like the previous letter, it is disingenuous and patronizing in its posture, criticizing and threatening the Cherokee with war and subsequent removal from their homeland.

Months later, Sevier became concerned that the murders of Red Bird and William Emery could become a National incident and lead to an untimely war for the newly formed country. On February 14, 1797, Sevier wrote to former governor William Blount, then in the United States Congress, informing him of the crime and naming Ned Mitchell and John Livingston as the murders. By March, Sevier clearly understood that citizens from Tennessee murdered Red Bird and William Emory in Kentucky, and he was solely accountable. On March 5, 1797, Sevier wrote to John Watts Jr. and other Chiefs of the Cherokee Nation, in response to their letter of March 4, 1797. While he did admit that it was his citizens who violated the United States Treaty, he begins the letter by accusing Chief Dick, a well known friend of Red Bird and William Emory, for committing acts in retaliation of their murders. On March 17, 1797 Sevier wrote a letter to Governor Garrard of Kentucky specifying Edward Miller and John Livingston as the murders of Red Bird and William Emory. On March 19, 1797, Sevier issues orders to the Sheriff of Hawkins County, Tennessee to apprehend the murderers of Red Bird and William Emory committed by Edward Mitchell and John Livingston, both citizens of the State of Tennessee and living in Hawkins County. It is important to note that Sevier was untruthful when he stated, “I am just now informed” of the murders. On March 28, 1797, Sevier wrotes to the Cherokee Nation further explaining that he has been requested by the Governor of Kentucky to have the two Tennessee citizens who murdered Red Bird and William Emory apprehended and sent to Kentucky to be tried for their crime. It is a fact, which Sevier has known for some time. While he admits the injustice to the Cherokee, it is not done without threatening them with war and removal. As a final letter on the subject, written on March 30, 1797, Sevier focuses on the killings by the Cherokee in retaliation for Red Bird and William Emory. For him, the matter of their murders is now closed.

John Sevier was re-elected for a second term as Governor of Tennessee between 1803 and 1809. During this time, the third and fourth Treaties of Tellico were negotiated and signed. The fourth treaty, signed on October 25, 1805, ceded Cherokee land in Kentucky, south of the Cumberland River. Among the Cherokee chiefs and headmen who signed the treaty were Kentucky born Taltsuska (Doublehead), phonetically written as Dhuqualutauge, Robert Benge’s oldest brother Ahuludegi (John Jolly), phonetically written as Eulatakee, and Dotsuwa (Red Bird), phonetically written as Tochuwor. By the time of the fourth Treaty of Tellico, it was likely that either one of Red Bird’s sons or nephews was given his name. Traditionally, names of a father or uncle are given in a naming ceremony before or after their death. Because the treaty ceded land in Kentucky and Red Bird was murdered in Kentucky during Sevier’s previous term, it was in the best interests of Indian agents Return J. Meigs and Daniel Smith to make sure that a descendant and namesake of Red Bird was represented.

About fifty-years after Red Bird’s murder, Lewis Collins published History of Kentucky. Much of Collin’s 1847 book reiterates the myths and sterotypes about the Indigenous people of Kentucky first introduced in John Filson’s 1788 The Discovery, Settlement, and Present State of Kentucke. Collin’s publication is largely devoted to Kentucky “Indian Fighters,” which most of the counties, cities, and towns are named after. Red Bird is one of the few exceptions. It is the name of towns in Bell, Clay, Whitley, and Wofford counties, and the namesake of the Red Bird River, a tributary of the Kentucky River. In consideration of this immunity, Collins wrote that Red Bird Fork and Jack’s Creek are named after two friendly Indians bearing those names, to home was granted the privilege of hunting there, they were both murdered for the furs they had accumulated, and their bodies thrown into the water. Unfortunately, Collins confused the names of Red Bird’s killer, Jack, with Red Bird’s friend, William Emory. Because Collin’s book serves as the foundation for all Kentucky history books that follow, his mistake became a historical fact, which has been told and written over and over again for more than 150 years.

About a hundred years following Red Bird’s murder, the Reverend Dr. John Jay Dickey, a Methodist minister, moved to southeastern Kentucky to help establish schools such as Lees Junior College in Jackson, Breathitt County, and Sue Bennett College in London, Laurel County. In the autumn of 1898, he was assigned service in several churches in Clay County including Fogertown, Hayden, Manchester, Paces Creek, and Wyatts Chapel. He was very interested in local family oral histories, which he recorded in his diary of more than 6,000 handwritten pages. Three of Dickey’s diary entries are specifically related to the murder of Red Bird. While each testimony contains a bit of truth, it is clear that they have been influenced by the distortions in Collins’ initial 1847 book, and its revised edition. Kentucky schoolteachers used the book in their history classes. On February 2, 1898, John Jay Dickey recorded the testimony of Captain Byron, in Manchester, Clay County, Kentucky. He noted the Cherokee Chief lived on Red Bird River near the mouth of Jack's Creek in this county. Byron also told Dickey that Red Bird lived with a crippled Indian named Willie (i.e., William Emory) and they were both shot to death. He added that their bodies were thrown into a hole of water known today as Willie's Hole, which were found by John Gilbert and others who buried them. Another oral tradition recorded by Dickey was that Red Bird was sitting on the bank of a creek fishing when he was shot and that he fell into the creek. On July 12, 1898, Dickey recorded the testimony of Abijah Gilbert, in Clay County, Kentucky who believed Red Bird was killed below the mouth of Big Creek. Gilbert also stated that only Red Bird was murdered and his companion had escaped. Also on July 12, 1898, Dickey recorded the testimony of John R. Gilbert, grandson and namesake of the person reported to have buried Red Bird. He placed the murder site at the mouth of Hector’s Creek. Unlike Byron’s testimony, he suggested that Red Bird was killed with his own tomahawk. His testimony also differed from his father’s suggesting that both Red Bird and his companion were murdered.

Roy White, the editor and publisher of the Manchester Guardian, was fascinated with the area’s history. White wrote a series of articles for the Clay county newspaper between May and December 1932. Although much of White’s information came from the Clay County Court Order Books, it is clear that all of his references to the murder of Red Bird were a recycling of of earlier publications.

Not long after World War II, Kentucky State Route 66 was dug across the narrow patch of ground in front of the rockshelter where Red Bird and Will were murdered. Because of the wet underlying shale, and its close proximity to the river, this portion of the road experienced seasonal landslides. To solve the problem, the Kentucky Department of Highways dug deeply into the shale immediately in front of the shelter. The traditional Cherokee symbols originally engraved at eye level were left hanging more than twenty feet above State Route 66. Fill from the highway excavations was used to make a small parking area between the shelter and river. In 1966, the Kentucky Historical Society and Kentucky Department of Highways erected a bronze State Historic Marker, Number 908, in the parking lot. While the purpose of the marker was to honor Red Bird, the text contains Collins’ original error in 1847 and was recycled by Collins and Collins in 1874, and White in 1932.

After the dedication of the State Marker, Fred Coy and Thomas Fuller 1969 examined petroglyphs at Red Bird’s murder site and gravesite. They concluded that the petroglyphs were quite different than any of those previously reported in the Commonwealth. The historic nature of the petroglyphs is evident in their sharply incised straight lines. They were likely carved with a sharp metal instrument such as a knife or tomahawk blade, rather than a ground-stone or flaked-stone tool. In 1989, the grave of Red Bird, known as the Red Bird River Shelter Petroglyphs site, 15Cy52, was added to the National Register of Historic places, Number 89001183. In 2003, the murder site of Red Bird, known as the Red Bird River Petroglyph site, 15Cy51, was also added to the National Register of Historic places, Number 89001182. Both sites are federally listed as religious and ceremonial sites. Riverbank erosion and seasonal landslides of the underlying shale continued into the 1990s. Following subsequent road improvements, a significant portion of the petroglyph bearing cliff-face at Red Bird’s murder site detached and fell to the ground. The State Marker was re-located to the campus of the Big Creek Elementary School, south of its original location on State Route 66. The rock containing the petroglyphs was moved to a park in Manchester, where it is currently protected beneath a pole building. When photographs of the petroglyphs taken when they were in place at the rockshelter site are compared to those on the rock in Manchester today, it is evident beyond a reasonable doubt that many of the traditional Cherokee symbols have been modified. Followers of the late Barry Fell, a self-proclaimed “epigraphic” expert, interpret the now modified petroglyphs as the inscriptions of ancient Greek Christians, a throwback to Filson’s 1788 argument that the Cherokee Nation has no valid claim to Kentucky because it was originally settled by an ancient white race that greatly predated them. Cherokee descendants of Red Bird frequently monitor the gravesite, as they have since his murder, and regularly pay homage to their ancestor in prayer ceremony. Recently, descendants found that the sites where Red Bird and William Emory were murdered and buried have sustained damage by grave robbers.

The Yahoo Falls Massacre

The Yahoo Falls Massacre

Yahoo is a local variation of the Cherokee word Yahula, which is a traditional Cherokee story about a mixed-blood trader who lived in a great stone house and was taken away by the Nunehi, the little people. Yahula would sing his favorite songs as the bells hanging around the necks of his ponies tinkled, echoing through the mountains along the Great Tellico Trail, today known as US route 27. The Great Tellico Trail extended from the Sequatchie Valley, near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, to the Cumberland River Valley of Kentucky, and beyond. The Alum Ford Trail, today known as State Route 700, connected the Great Tellico Trail with east-central Tennessee by way of an enormous sandstone rock shelter located behind Yahoo Falls, one of the tallest waterfalls in the state.

According to traditional Cherokee story tellers, one day, all the warriors left on a hunt, but when it was over and they returned, Yahula was nowhere to be found—the Nunehi had taken him to the Spirit World. While he was there, Yahula made the mistake of eating the food of the Nunehi, which meant that he could never return to his people except as a Spirit. Although he was never seen again, the Cherokee believe that the songs of Yahula and the tinkling bells of his horses can still be heard at night near the running water of Yahoo Falls located in the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, McCreary County, Kentucky. On the Trail of Tears, the story of Yahula was used to urge the people forward to Oklahoma, suggesting that Yahula has gone there and we will hear him, but they never did. The story of Yahula is hauntingly similar to the story of Jacob Troxell and the massacre of Yahoo Falls.

In the winter of 1777-1778, Jacob Troxell, also known as Big Jake because of his height, was a private in the Continental Army at Valley Forge under the command General George Washington. Jacob Troxell, born in 1758, was the son of a Jewish immigrant from Switzerland and his mother was Delaware. In February 1778, word reached Washington that British forces had abandoned the old French Post Vincennes in present day Indiana, and it was in the hands of American militia. Cherokee, Miami, Piankeshaw, and Shawnee, along with Jesuits, Voyagers, and traders were using it. Washington’s staff assigned Jacob Troxell to pose as a trader and go to Post Vincennes to persuade as many American Indians as possible to support the Continental Army in their war against the British.

At Port Vincennes, Jacob Troxell befriended a young Cherokee warrior about his same age from the Cumberland River valley, Tukaho Doublehead, son of Taltsuska (Doublehead) and Creat Priber. Doublehead was born in McCreary County, Kentucky, son of Wilenawa (Great Eagle), grandson of Moytoy, and great-grandson of Amatoya Moytoy—a fourth generation Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Tukaho invited Jacob Troxell to his village, Tsalachi, which was located near present-day Burnside, Kentucky. In the summer of 1779, Doublehead welcomed his son’s new friend and invited him to stay and trade with his people. Not long afterwards, Jacob Troxell became smitten over one of Doublehead’s four daughters.

During the winter of 1779-1780, Tory infantry from Watauga, under the command of Major Patrick Ferguson, British Commander of the 71st regiment, were robbing and killing Cherokee hunters as they traversed the Great Tellico Trail. Jacob Troxell accompanied Doublehead and his daughter in their attack on a Tory camp on the Little South Fork, in what is today Wayne County, Kentucky. He used the incident to explain why Doublehead and his warriors should support Washington and the colonial army. Jacob Troxell successfully completed his mission. At the decisive Battle of Kings Mountain, October 7, 1780, there were Cherokee warriors fighting against the British. Among them was King David Benge, nephew of Red Paint Clan Mother, Wurteh, granddaughter of Doublehead, and first cousin of Sequoyah.

Following the end of the American Revolution, Jacob Troxell married the sister of Tukaho and soon had a son known as Little Jake. By this time, Cherokee living in the Cumberland River valley were almost unrecognizable to the whites now settled in the area. Jacob Troxell and his family, like other Cherokee, lived in a cabin, herded cattle, horses, and pigs, and used metal farming tools to tend crops of potatoes, native corn and beans, orchards of peach trees, and they kept bees for honey and wax for trade. By this time, Doublehead had built an estate near Muscle Shoals, Tennessee. His estate included twenty enslaved African Americans and at least one mixed blood, thirty head of cows, 100 head of fine stock cattle, two stud horses, eight mares and geldings, and nine head of common horses, fifty head of sows, pigs and small stock hogs, and 100 head of large hogs. His home was furnished with four large beds with contemporary bedding and bedsteads, six dining room and twelve sitting chairs, dining room and kitchen tables, dishes and tableware, large and small iron cooking pots, a brass kettle and teapot, three large ovens, and three pair of iron fire dogs. Doublehead’s immense fortune was thought to have come from money that he skimmed from treaty entitlements.

News of Doublehead’s murder in 1807 spread across the Great Tellico Trail and into the Cumberland River valley. Without the protection of his powerful father, Tukaho Doublehead was powerless and vulnerable. His people were greatly reduced in number and dispirited from fighting off the advance of white settlers and smallpox. To make matters worse, Tukaho Doublehead had married a white woman, Margaret Mounce, from Cherry Fork, present-day Helenwood, Tennessee. The prejudice and hatred of Doublehead’s people grew among European settlers. They hunted down and murdered Jacob Troxell’s brother-in-law, Tukaho Doublhead atop a ridge that still bears his name, Doublehead Gap, in present-day Wayne County, Kentucky.

On January 15, 1810, the “War Hawks” of Congress expressed concern about the Indian presence in Kentucky and extinguished all Cherokee land claims in the state. Although the Cherokee in the Cumberland River valley had made every possible concession to maintain peace with the United States, many of the European settlers were former Franklinites, followers of John Sevier. The European settlers’ hatred of the Cherokee grew, in part, out of their indifference between those who fought Shawnee in the Northwest Territory against Kentucky troops at Fallen Timbers, Tippecanoe, and the River Raisin, and those who fought alongside American forces in the Southeast against the Creek at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Expecting the worse, Tukaho Doublehead’s sister, Jacob Troxell’s wife, realized that the only way her people could survive would be if they moved south on the Great Tellico Trail. Between 1803 and 1804, her father had helped Reverend Gideon Blackburn, a Presbyterian pastor from Jacob Troxell’s hometown of Philadelphia, open a school on Cherokee land near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee. In the late summer of 1810, Blackburn agreed to offer protection and education to all Cherokee women and children from the Cumberland River valley. Doublehead’s daughter sent Little Jake on horseback to spread the word that anyone seeking protection at the Blackburn school in Chattanooga should meet in the rockshelter behind Yahoo Falls when the moon was full and round.

All that remained of Doublehead’s people in the Cumberland River valley, mostly women and children, gathered at Yahoo Falls. They waited for Doublehead’s daughter and her son, Little Jake, to arrive and lead them to safety. Fearing that she was not going to show up, some of the mothers gathered their children, shouldered their packs, and began to walk out of the shelter. A volley of gunfire erupted from the darkness in front of the falls. A local militiaman, Hiram Gregory, had learned of the gathering behind Yahoo Falls, enlisted a group of young vigilantes, and set out to exterminate the Cherokee from the Cumberland River valley once and for all. Gregory’s mercenaries focused their initial attack on the few warriors that were present, and then they been began to slaughter the women and their children. Campfires illuminated the shelter leaving the Cherokee completely open and exposed—there was nowhere for them to run or hide. After it was all over, more than 100 Cherokee lay dead or dying behind Yahoo Falls. Doublehead’s daughter died from injuries received during the massacre. She was buried at the base of a large flat stone in what is today Stern’s Kentucky, the birthplace of her father. Jacob Troxell was said to have lost his mind in grief. A mass grave was excavated in a high terrace behind the falls, the only place where the soil was deep enough to dig a trench. The bodies of the slain Cherokee men, women, and children were laid to rest until the grave was exposed during logging operations during the early twentieth century.

The exact date of this horrific event is unknown. Some say that the massacre occurred on the 130th anniversary of the Pueblo Revolt, August 10, and others have placed it in the fall, early October. Regardless of the exact day and month, all of the published documents and family histories agree that the massacre of Yahoo Falls took place in the latter half of the year 1810. There is a similar misunderstanding on the date and place of death of Big Jake Troxell. Although the military tombstone along SR 700 reads Jacob Troxell, Pennsylvania, Pvt, 6 Co., Philadelphia, Co. Militia, Revolutionary War, January 18, 1758, October 10, 1810, family records indicate that he was taken to Alabama where he lived until 1817. If he suffered catatonic depression following the death of his Cherokee wife as reported, then he would have been considered a living dead man, a person whose body was alive, but his spirit had left him, a situation not unlike the trader in the story of Yahula.

There is also great deal of confusion about the death of Doublehead. What most people missunderstand is that there were many Cherokee named Doublehead because all of his thirteen children with four wives were named Doublehead—Tukaho Doublehead, Tuskiahoote Doublehead, Saleechie Doublehead, Nigodigeyu Doublehead, and Gulustiyu Doublehead with Creat Priber—Bird Tail Doublehead and Peggy Doublehead with Nannie Drumgoole—Tassel Doublehead, Alcy Doublehead, and Susannah Doublehead with Kateeyeah Wilson—Two Heads Doublehead, Doublehead Doublehead, and William Doublehead with an Cherokee woman whose name is unknown. Because Tukaho Doublehead’s murder occurred in the same year as his father, 1807, the two events have been confused. Chief Doublehead was murdered in Tennessee and Tukaho Doublehead was killed in Kentucky.

Perhaps the biggest problem with all versions of the massacre, both written and oral histories, is that Jacob Troxell’s wife, Tukaho’s sister, Doublehead’s daughter, was named “Princess Corn-blossom.” The first problem with the name Princess Corn-blossom is that there was no such thing as a “Cherokee Princess.” The term came from the time when Moytoy (1730-1760) was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee. Sir Alexander Cuming proclaimed him as King of his people. If Moytoy was a King, then his daughters must have been princesses. Doublehead was the son of Great Eagle, who was the son of Moytoy, and tribal leadership was passed down from father to son. Princess is the way eighteenth century British communicated the kin term daughter of a Chief. Secondly, the name Corn-blossom is not a Cherokee word. While Corn-tassel (Utsidsata and Onidosita) and Corn-silk (Seluunenudi) are Cherokee words that approximate Corn-blossom, they are masculine names. One of Doublehead’s children by Kateeyeah Wislon was named Tassel. Unfortunately, the gender of the offspring is unknown and was not born until about 1798.

Cherokee census and enrollment records indicate that Doublehead had four daughters living with him at the time Tukaho brought Jacob Troxell to Tsalachi and they were all very close in age—Tuskiahoote, Saleechie, Nigodigeyu, and Gulustiyu respectively. Tuskiahoote and Saleechie were both reported as the wives of Colonel George Colbert, and Nigodigeyu and Gulustiyu were reported as the wives of Samuel Riley. We can rule out Saleechie Doublehead because it is well documented that she survived the Trail of Tears and died in Indian Territory, Oklahoma in 1846. Tuskiahoote Doublehead is thought to have lived until 1817, but we cannot rule her out because this date is by no means a certainty. It is also interesting that Tuskiahoote Doublehead’s death date not only matches that of Jacob Troxell, she reportedly died in Alabama.

Samuel Riley is an especially interesting character because he seized most of Chief Doublehead’s personal property after his murder in 1807. Furthermore, he was known as the "White Patron" of Gideon Blackburn's School, the same school Doublehead’s daughter was taking the Cherokee of the Cumberland River valley to at the time of the massacre. Although Riley is reported to have fathered five children by Nigodigeyu and eleven by Gulustiyu, it is quite possible that he falsely claimed two wives in order to ensure his entitlements to Doublehead’s fortune. On April 28, 1819, Riley filed a suit for Doublehead’s entitlements, about fifteen days before he succumbed to an illness. He is assumed to have been Doublehead’s son in law solely on the basis of his last will and testament, which was accepted by the Supreme Court of the Cherokee Nation on October 25, 1825, as recorded by John Martin.

On January 31, 1811, just months after the Yahoo Falls massacre, the former Cherokee land was granted for sale at the minimal price of ten cents an acre in order to encourage the development of iron and salt works. As salt was an expensive commodity at $25.00 a barrel, the families who had orchestrated the Yahoo Falls massacre purchased the land containing salt springs and became rich.

During the first forty years of the 20th century, blight devastated the American chestnuts. Although the blight provided an economic boom to the local timber industry, logging operations deforested the shallow unstable soils around Yahoo Falls. Unprecedented erosion extended into the great sandstone rock shelter behind the falls and exposed a mass grave filled with human skeletal remains. Grave robbers, artifact collectors, curiosity seekers, and gravity began to disperse bones down slope until it was impossible to walk into the shelter without stepping on them. All that survives is an empty trench behind the falls, which approximates the size of the mass grave at Wounded Knee Memorial on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Today, Yahoo Falls is located in the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, National Park Service, McCreary County, Kentucky.

The Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which ordered the removal of all American Indian tribes living in the east to lands west of the Mississippi River. Although it was successfully challenged by the Cherokee Nation and declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court, then President Andrew Jackson refused to recognize the decision. His refusal to enforce the court's verdict resulted in the expulsion of more than 16,000 Cherokee from their homes. The paths of removal through Kentucky are known to the Cherokee as the Trails Where They Cried, also known as the Trail of Tears.

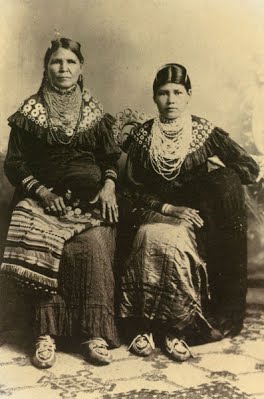

The Cherokee were forced to move out of Kentucky on three routes, one by water and two by land. About 3,000 Cherokee traveled out of Kentucky by river to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. On June 6, 1838, a steamboat and barge made its way from Ross's Landing on the Tennessee River, today known as Chattanooga, Tennessee, through western Kentucky to the Ohio River, on to the Mississippi and Arkansas rivers, and finally on into Oklahoma. Extreme drought and disease resulted in many deaths, especially for the children and elderly. The remaining Cherokees traveled out of Kentucky overland on dirt roads in multiple detachments, upwards of 1,600 each. John Benge was one of the detachment conductors appointed by then Cherokee Principal Chief, John Ross. A combination of insect filled flour and corn, tainted meat, lung ailments, and drought made travel through the state extremely difficult and resulted in the death of an untold number of Cherokee. The exact death toll is impossible to calculate, but it clearly was in the thousands.

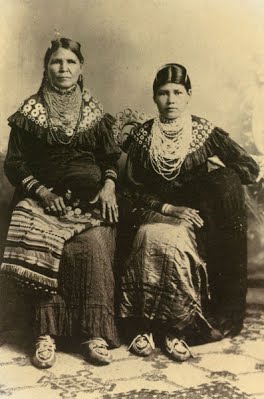

In 1830, at the time of the Indian Removal Act, remnants of the Cherokee lived along Little Goose Creek, in Clay County, which was the dividing line between the Cherokee and Euroamerican settlers. Some of the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears escaped and secretly joined their extended families in Clay County. Since then, Cherokee families living in Kentucky have been subjected to ethnocide. Ironically, outside of their reserve lands in North Carolina and Oklahoma, there are more people of Cherokee descent living in Kentucky than any other state.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. It includes a park in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, which is one of the few documented campsites used on the Trail of Tears. In 1996, the National Park Service certified the campsites used between 1838 and 1839 as part of the National Historic Trail of Tears, the only non-federally owned property with this title. Of particular significance, the Hopkinsville, Kentucky park includes the graves of Fly Smith and Whitepath, Cherokee Chiefs who died during the removal.

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Historically, the Piqua, also spelled Pekowi and Pekowitha, was a division of the Shawnee. The name Piqua literally translates into American English as “made of ashes.” The word originates from a Shawnee phoenix creation story in which a man rises from the ashes. Some Shawnee have also translated Piqua as the dusty feet people. The Piqua were known as the second oldest brother of the five brothers or bands of the Shawnee. They were also known as the talking band because they arranged for the speakers for the Principal Chief.

In 1774, colonial troops fought the Piqua Shawnee under the leadership of Cornstalk in the battle known as Point Pleasant, West Virginia. With the death of Cornstalk, they, like the Cherokee, became split in their support of the American Revolution. By 1778, most of their towns in Kentucky such as Eskippakithiki, today known as Indian Old Fields in Clark County, had been repeatedly destroyed by the American army. According to the Draper manuscript, many Piqua Shawnee moved from Lower Shawnee Town, in present-day Greenup and Lewis counties, Kentucky to a village near the mouth of the Little Miami River in present-day Hamilton County, Ohio. Archaeologically, this site is known as the Fort Ancient Madisonville site. In addition to European trade goods and French gunflints, radiocarbon dating demonstrate that the site was indeed occupied at that time by the Shawnee. Interestingly, the Madisonville site also produced numerous copper pendants and engraved bone artifacts as well as what may be one of the largest serpentine-shaped earthworks ever discovered. The importance of the snake symbol is illustrated by the fact it was often used as a tribal sign on eighteenth century Shawnee treaties. It is quite possible that the earthwork represents a marker for Manato, the snake clan, and the Madisonville site may have been a Shawnee Snake Town.

Fort Ancient livelihood combined farming, hunting, and gathering. Domesticated plants such as beans, gourds, maize, squash, and sunflower were grown, and their diet was supplemented with small game hunting and wild plant gathering. Fort Ancient agricultural land was well-planned and maintained with staggered planting to reduce the risk of crop failure. They stored their agricultural produce in abundant voluminous bell-shaped storage pits, which allowed them to seasonally leave their villages to make salt and hunt game such as bear, bison, deer, elk, and turkey at places such as Big Bone Lick, Kentucky.

Recent DNA studies suggest that the ancestry of the Piqua Shawnee may extend even further back in time. Of the five mitochondrial DNA haplogroups found among all Native Americans (i.e., A, B, C, D, X), haplogroup A has been found in high frequency among living Shawnee and Woodland populations that date between 500 BC and AD 500. This finding may be related to the initial movement of Shawnee into the North.

Today, the Piqua Shawnee speak an Algonquian language related to that of the Chippewa, Fox, Kickapoo, Sauk, and other American Indians of the Ohio River valley. Their kinship is patrilineal, which means that group descent and tribal affiliation is inherited through the father’s family. Oral histories and traditional ways of life were passed down generation after generation from those who escaped the forced removal during the 1830s. In 1991, the Governor of Kentucky recognized the Piqua Shawnee as an American Indian tribe indigenous to Kentucky, and the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission under the authority of the Davis-Strong Act recognized the Piqua Shawnee as an American Indian tribe in the state of Alabama. The Piqua Shawnee have reserve land along the Warrior’s Trail in Jackson County, Kentucky. Tribal members gather there four times a year for Winter and Summer Council meetings, Spring and Fall Bread Dances and Ceremonies, and the Green Corn Dance and Ceremony. Today, the Piqua Shawnee are the only recognized tribe in Kentucky.

American Indian Legislation

American Indian Legislation

American Indians in Kentucky were not considered human until 1879, when Standing Bear, a Ponca filed a Writ of Habeas Corpus in the District Court of the United States. His case set precedence for American Indians living in Kentucky and elsewhere the United States. However, most American Indians in Kentucky were not considered citizens until 1924. Before then, some American Indians living in Kentucky acquired citizenship by marrying Euroamerican men or through military service. Most American Indians living in Kentucky were barred from citizenship until the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act was passed.

Further steps toward the recognition of American Indians in Kentucky began with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NRHPA) of 1966, signed into Public Law by President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Through the NHPA, a National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) was created, which documents historically significant American Indian places, objects, and culture. It also provided funding to establish a State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO) and staff to conduct surveys, undertake comprehensive preservation planning, and establish standards for programs in each state. The NHPA also required all states to establish a mechanism for certifying local governments to participate in the National Register nomination and funding programs. In response to the NHPA, Governor Edward Breathitt created the Kentucky Heritage Council (KHC) in 1966 as an agency of the Commerce Cabinet. One of the directives of the KHC is to identify, preserve, and protect all meaningful American Indian cultural resources in the state. The KHC subsequently focused its efforts on the documentation and preservation of vestiges of American Indian artistic and cultural resources from hundreds and even thousands of years ago. Contemporary American Indians, tribes, and organizations in the state were essentially ignored because they were not included in the original composition of the NHPA.

Visibility of American Indians in Kentucky began to change with the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), which was signed into Public Law by President James Earl Carter Jr. on August 11, 1978. Not only does the AIRFA protect and preserve the inherent right of all American Indians and tribes to believe, express, and exercise traditional religions and use items of artistic and material culture that are considered sacred, it also provides American Indians with unlimited access to sacred sites, including those in Kentucky that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Unfortunately, these sites also attracted the attention of grave robbers and plunderers for profit. In 1987, the repugnantly large-scale pillaging of an American Indian cemetery near Uniontown, Kentucky brought international attention to the American Indian people, tribes, and organizations in the Commonwealth when they spoke out against the desecration. The outcome was a positive change in laws concerning the protection, preservation, and conservation of these sacred places. Most notably was the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) signed into federal law by President George Bush Sr. on November 16, 1990. NAGPRA provides a process for the return of human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to Indigenous lineal descendants and culturally affiliated tribes.

By 1996, the NHPA had been amended many times to include American Indians, tribes, and organizations in partnership with State and Federal government to provide leadership in the preservation of cultural resources. The amendments were specifically made to assist American Indians in the expansion and acceleration of historic preservation programs and activities. The intention of the amendments was to foster communication, cooperation, and coordination between American Indians and the SHPOs in the planning and administration of the NHPA. These activities include the identification, evaluation, protection, and interpretation of historic properties. The new amendments to the NHPA allow cultural items and properties of traditional religious and cultural importance to American Indians, tribes, and organizations to be protected and eligible for inclusion on the NRHP. The amendments to NHPA made it essential that all preservation-related activities, including planning, are carried out in consultation with Indigenous people, tribes, and organizations.

In 1996, First Lady of Kentucky, Judi Conway Patton, a person of native heritage, felt strongly that American Indians, tribes, and organizations should be represented in the KHC and state government. At her urging, Governor Paul Edward Patton established the Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission (KNAHC) as an advisory board attached to the Education, Arts, and Humanities Cabinet (EAHC), and authorized by Executive Order 96-272 on March 5, 1996. Since the creation of the KNAHC, Kentucky has participated in the Governor’s Interstate Indian Council (GIIC), a national organization established in 1949 by the National Governors' Association to promote and enhance government relations between Tribal Nations and the states. Its mission is to bring respect and recognition to the individual sovereignty of Tribal Nations and states. The GIIC also supports the preservation of traditional American Indian culture, language, and values, and to encourage socioeconomic development aimed at tribal self-sufficiency.

In an effort to acknowledge all American Indian people, tribes, and organizations in Kentucky, Governor Paul Edward Patton signed House Bill 801 on April 7, 1998, which designates November as Native American Indian Month. House Bill 801 not only recognizes that American Indians are important to the state’s history, playing a vital role in enhancing the freedom, prosperity, and greatness of the state, it also reflects the Commonwealth's commitment to American Indians as an integral part of the social, political, and economic fabric of the state of Kentucky. On April 2, 2004, Governor Ernie Fletcher, a person of native heritage, signed House Bill 167 into law. House Bill 167 was written by Reginald Meeks and passed by both houses. It ensures that the KNAHC is a permanent part of the Governor’s cabinet to promote awareness of Indigenous influences within the historical and cultural experiences of Kentucky.

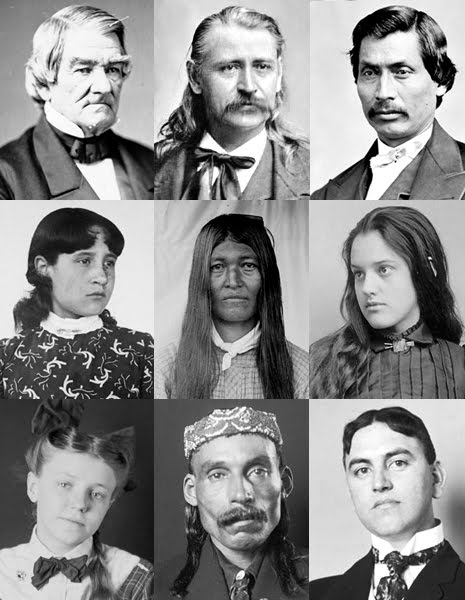

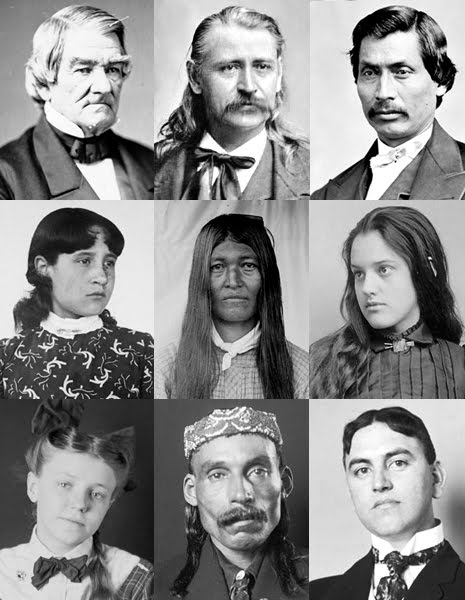

Notable American Indians

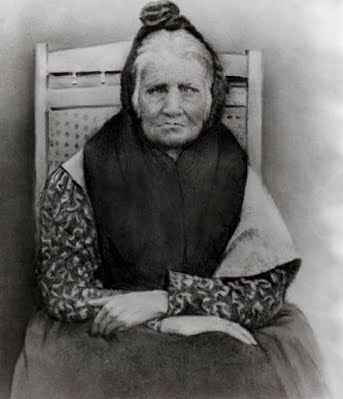

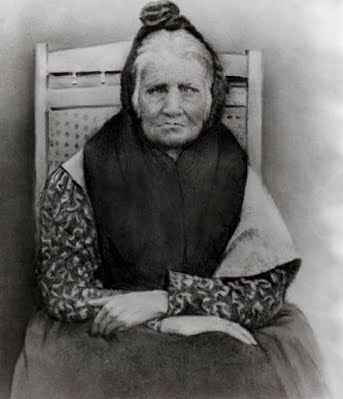

- Nonhelema (1720-1787) A female Piqua Shawnee Chief.

- Red Bird (1721-1796) Also known as Dotsuwa, he inscribed traditional Cherokee symbols on the walls of rosckshelters in Spurlock, Kentucky. He is the namesake of the Red Bird River and several towns in Kentucky. He was murdered in Clay County, Kentucky by two men from Tennessee, Edward Miller and John Livingston, an incident of National significance.

- Blue Jacket (1737-1808) Last principal War Chief of the Shawnee, Piqua Division, Rabbit Clan, and given the name Sepettekenathe, Big Rabbit. His chosen name was Waweyapiersenwaw, Whilpool. He signed the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 and the Treaty of Fort Industry in 1805.

- Black Hoof (1740-1831) Also known as Catahecassa, he was born near Winchester, Kentucky, and became principal Chief of the Shawnee. He was present at Braddock’s defeat in 1755, and played a significant role in the battle of Point Pleasant. He is best known as a Shawnee leader who emphasized peace.

- Doublehead (1744-1807) Also known as Dsugweladegi and Taltsuska, was born in Sterns, Kentucky. He served as Principal Chief of the Cherokee and signed multiple treaties with the United States, which ceded significant portions of tribal land and resulted in his blood oath murder on the Hiawasse River in Tennessee.

- Jesse Brock (1751-1843) Son of Dotsuwa, Red Bird, he was a Cherokee scout during the American Revolution and present at Yorktown when Cornwallis surrendered. He lived in Wallens Creek in Harlan County, Kentucky.

- David Benge (1760-1854) Also known as King David Benge, he was the first cousin of Robert Benge and Sequoyah. He served during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, fighting in the battles of Kings Mountain and Thames.

- Robert Benge (1766-1794) Also known as the Bench, he was a red-headed Chickamauga War Cherokee Chief, half-brother of Sequoyah and son of John Benge and Red Paint Clan Mother, Wurteh Watts.

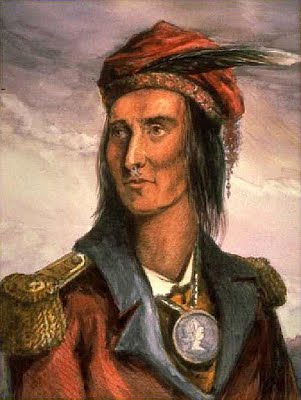

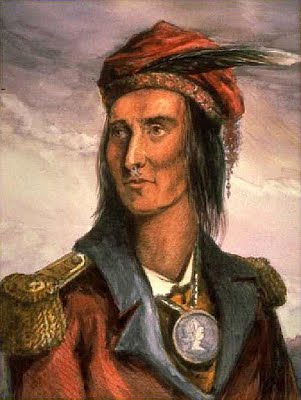

- Techumeh (1768-1813) Also known as Tikamthi and Tecumtha, Sky Panther, he was born in the Piqua Shawnee village on the Mad River, which was destroyed by Kentucky militia in 1780. He called for a unification of all Indian people west of the Appalachians, denouncing alcohol, fighting between American Indian groups, and the ways of Europeans. Together with his brother the Prophet, they founded Prophetstown where the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers meet in Indiana. But their movement to found a unified American Indian nation disbanded after their defeat in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811.

- The Prophet (1775-1837) Also known as Tenskwatawa, brother of Tecumseh, he was a self proclaimed spiritual leader of the Shawnee whose influence spread as far south as the Southern Creek and Siksika. He had more than 1,000 converts, and his teachings helped create a northern confederacy that held together until the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811.

- Sequoyah (1778-1844) Also known as George Guess and George Gist, the single most well-known Cherokee who standardized a system of writing that is still in use today. He was the son of Nathaniel Gist and Red Paint Clan Mother, Wurteh Watts. His earliest known writing can be found inscribed in stone at the grave site of Red Bird in Clay County, Kentucky.

- John Benge (1788-1854) Chickamauga Cherokee Chief, he was the son of Robert Benge. He served in Morgan’s Cherokee Regiment during the War of 1812. He voted against removal and served as a wagon-master on the Trail of Tears.

- Tassel Doublehead (1798-1807) Also known as Tukaho, he was the son of Chief Doublehead and Kateeyeah Wilson. He was murdered and is buried on a mountain top in Wayne County, Kentucky, known today as Doublehead’s Gap.

- William Benge (1799-after 1860) Also known as Booger Bill Benge, he was the son of King David Benge. He performed the Cherokee Booger Stomp dance in Great Salt Petre Cave in Rockcastle County.

The Land Of Swinging Bridges

The Land Of Swinging Bridges

Project Hope began when a group of people, seeing that Clay County was in need, formed to repair and paint buildings, sweep sidewalks, and organize community garbage pickups. As they listened to citizens they saw the need to involve youth. It became Project Hope's focus to involve youth in improving the community. Projects have included the middle school art class painting of a "Welcome to Clay" mural, teaming up with VOA and the leadership team of CCHS to create a "Hope Endures" mural, and revitalizing the basketball courts during Covid. A Flag Project promotes a sense of pride in the community for our country, funded entirely through community donations. Project Hope has also hosted a ceremony for area veterans, hosted Christmas parades, and organized Tour of Lights; all Covid friendly events. The organization jumps in wherever there is a need.

Project Hope began when a group of people, seeing that Clay County was in need, formed to repair and paint buildings, sweep sidewalks, and organize community garbage pickups. As they listened to citizens they saw the need to involve youth. It became Project Hope's focus to involve youth in improving the community. Projects have included the middle school art class painting of a "Welcome to Clay" mural, teaming up with VOA and the leadership team of CCHS to create a "Hope Endures" mural, and revitalizing the basketball courts during Covid. A Flag Project promotes a sense of pride in the community for our country, funded entirely through community donations. Project Hope has also hosted a ceremony for area veterans, hosted Christmas parades, and organized Tour of Lights; all Covid friendly events. The organization jumps in wherever there is a need.

Monkey Dumplins Story Bridge Theater

Monkey Dumplins Story Bridge Theater Experience Elk Country

Experience Elk Country Early 19th Century

Early 19th Century The U.S. Civil War

The U.S. Civil War Stereotypes

Stereotypes Arts & Crafts

Arts & Crafts

Perhaps the most exciting method of transportation was by freight boat down the Kentucky River. Much of east central Kentucky was supplied in this way. Boats were built near the works by laborers from material cut with whipsaws driven by water power. They were substantial craft with a walk-way from end to end along each side. They could be run only when a freshet was on the streams, and when travel was slow, they were hurried along somewhat by means of poles. A man would step to the front end of the walk-way, set one end of a long pole against the bottom of the stream, with the other end resting in his hand laid against the pushing shoulder, and walk to the stem of the boat, pushing all the while, whereupon he would return to the prow of the boat and repeat the walk.

Perhaps the most exciting method of transportation was by freight boat down the Kentucky River. Much of east central Kentucky was supplied in this way. Boats were built near the works by laborers from material cut with whipsaws driven by water power. They were substantial craft with a walk-way from end to end along each side. They could be run only when a freshet was on the streams, and when travel was slow, they were hurried along somewhat by means of poles. A man would step to the front end of the walk-way, set one end of a long pole against the bottom of the stream, with the other end resting in his hand laid against the pushing shoulder, and walk to the stem of the boat, pushing all the while, whereupon he would return to the prow of the boat and repeat the walk.

As the enrollment grew, Burns turned students away because they couldn’t find lodging in nearby homes. In 1905 he arranged to start the construction of a girls’ dormitory while he raised the money. He made the rounds across the state to any church that would listen to his story. Burns said in The Crucible, “Somehow the payrolls were always met. Bob Carnahan took care of any overdrafts. In due time Carnahan Hall was completed and a home for 50 girls was provided.”

As the enrollment grew, Burns turned students away because they couldn’t find lodging in nearby homes. In 1905 he arranged to start the construction of a girls’ dormitory while he raised the money. He made the rounds across the state to any church that would listen to his story. Burns said in The Crucible, “Somehow the payrolls were always met. Bob Carnahan took care of any overdrafts. In due time Carnahan Hall was completed and a home for 50 girls was provided.”

Native Americans of Clay County & Kentucky

Native Americans of Clay County & Kentucky

European Contact

European Contact Changing Alliances

Changing Alliances Chief Red Bird

Chief Red Bird The Yahoo Falls Massacre

The Yahoo Falls Massacre The Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Piqua Shawnee Tribe American Indian Legislation

American Indian Legislation